Environmental, Natural Resources, & Energy Law Blog

New York Public Service Law Article X, Renewable Energy Projects and NIMBY - Kate McCurdy

Open gallery

New York State is anxious to lead the shift towards renewable energy. As one of the most populous states in the U.S. and home to its largest city, New York consumes a lot of electricity. Governor Andrew Cuomo has announced the goal of having New York’s electricity sourced from 70% renewable energy by the year 2030. https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All-Programs/Programs/NY-Sun/Solar-Data-Maps (last visited Nov. 1, 2020). Part of this initiative is a $1 billion investment of state funds into solar farm initiatives. Id. Of course the next question is “where will all of these farms be located?”

This blog post reviews New York State’s electric generation facility siting laws and the “Not-In-My-Backyard” (“NIMBY”) problems that led to the current siting procedures. New York has a particular tension between the needs of the greater New York City area (“Downstate”) and the availability of cheap land in the economically disadvantaged remainder of the State (“Upstate”). The State government currently has, in practical terms, complete authority over siting of solar farms, wind turbines and other electric generating facilities. I argue that the State should have broad authority make these decisions, but the effects of these projects on the local landowners should be mitigated and some benefit should be provided to those who own land that is adjacent to the site.

NYS PUBLIC SERVICE LAW ARTICLE X

New York State Public Service Law Article X was originally enacted in 1992, mostly to address the issue of power plant siting. David Ehrlich, Powering the Permit Process: A Mixed Review of Article X, 6-Fall Alb. L. Envtl. Outlook 19, 19 (Fall, 2001). The idea was to provide a uniform approval process for utility companies across the state and ensure the State government maintained control of the approval process. Id. That way, New York State could oversee proper environmental assessments for each project, and each utility company did not have to work through the mosaic of local municipalities for approval. Id. The statute established a state board with the sole purpose of approving or disapproving siting for electric generation facilities, and board’s decisions were only subject to judicial review under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard. Gregory D. Eriksen, Breaking Wind, Fixing Wind: Facilitating Wind Energy Development in New York State, 60 Syr. L. Rev. 189, 194 (2009). The board was comprised of the Chairman of the Department of Public Service, the Commissioner of the Department of Environmental Conservation, the Commissioner of Health, the Chairman of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, the Commissioner of Economic Development, and two ad hoc members from the local municipality in which the facility was intended to be sited. David Ehrlich, Powering the Permit Process: A Mixed Review of Article X, 6-Fall Alb. L. Envtl. Outlook 19, 19 (Fall, 2001).

Article X contained a sunset provision, and eventually lapsed in 2003 when the legislature failed to pass its renewal. Gregory D. Eriksen, Breaking Wind, Fixing Wind: Facilitating Wind Energy Development in New York State, 60 Syr. L. Rev. 189, 193 (2009). Between 2003 and 2010, a hybrid of state and local processes determined the sites of electric generation facilities. By this time, wind turbines projects were gaining traction. The first step in the siting review process during these years involved the selection of a “lead agency” based on the scope of the project and its anticipated impacts. Id. at 195. If the impacts were statewide, then a State government agency would conduct the review. If the impacts were largely of “local significance,” then the municipality of the intended site served as the lead agency. Id. It was not clear to me which body or person made the determination that a project had “local” vs. “statewide” impacts, nor was it clear which factors were considered while making this determination. The lead agency would determine if an Environmental Impact Statement was required from the utility company before the project would be approved. Id. Wind energy projects generally always required formal Environmental Impact analysis before construction could begin. Id. Similarly to Article X, developers were required to mitigate any potentially adverse environmental impacts. Id. After a public comment period, the lead agency (i.e. local municipality) would consult with other involved state and local agencies to determine if the project could move forward. Id. In this regime, local municipalities had tremendous power to determine the extent of the EIS required, and the ability to approve or disapprove of the project overall. The judicial review could only look at whether the lead agency’s determinations were made “in violation of lawful procedure, was affected by an error of law or was arbitrary and capricious or an abuse of discretion.” Id.

As one may expect, momentum dwindled for the construction of renewable electric generation facilities. Local municipalities did not want large wind turbines constructed in their areas and the state had lost its control over the process.

In 2011, New York State Public Service Law Article X was reenacted, and it remains in force today. McKinney’s NYS Pub. Serv. Law §168 (Aug. 4, 2011). In this version, the seven-member board make-up remained the same. However, the legislature buried a key change in §168(3)(e). The Board can grant a certificate for the construction of an electric generation facility as long as the facility is designed “to operate in compliance with applicable state and local laws and regulations issued thereunder… except that the board may elect not to apply, in whole or in part, any local ordinance, law, resolution or other action or any regulation issued thereunder…if it finds that, as applied to the proposed facility, such is unreasonably burdensome…” NYS Pub. Serv. Law §168(3)(e) (emphasis added). This means that the siting board can opt out of local laws that may be designed to keep these construction projects out of their area. The board approvals are made project-by-project, and each application process includes a public hearing where the residents and municipalities can air their grievances to the board for consideration. Id. However, the siting board has the ultimate authority to approve sites.

Significantly, the burden is on the municipality to show the board that the opted-out law or regulation is not “unreasonably burdensome.” Id. If a town enacts zoning laws that prohibit the construction of a large electrical facility and the siting board chooses to ignore the zoning laws to provide the certificate under Article X, the State does not need to show why it is ignoring the zoning law. No evidence is required for the State to make such a determination that the zoning law is unreasonably burdensome – the town must bring an action in court to show the zoning law is not unreasonably burdensome to prevent the construction from moving forward. This is a drastic shift from the municipal control regime between 2003 and 2011. Now the State has almost complete control, and municipalities must overcome significant legal hurdles to prevent a siting.

Both the old and new versions of Article X require the applying utility company to contribute to an “intervenor fund,” which is to be disbursed to interested local and municipal parties, at the board’s direction, to cover expert witness and consultant fees. David Ehrlich, Powering the Permit Process: A Mixed Review of Article X, 6-Fall Alb. L. Envtl Outlook 19, 19 (Fall, 2001). Attorney’s fees are explicitly denoted as expenses the intervenor fund will not cover for interested parties. Id. Attorney fees to challenge the project or advocate for the municipality or interested local group must be sourced elsewhere.

THE DICHOTOMY IN NEW YORK STATE

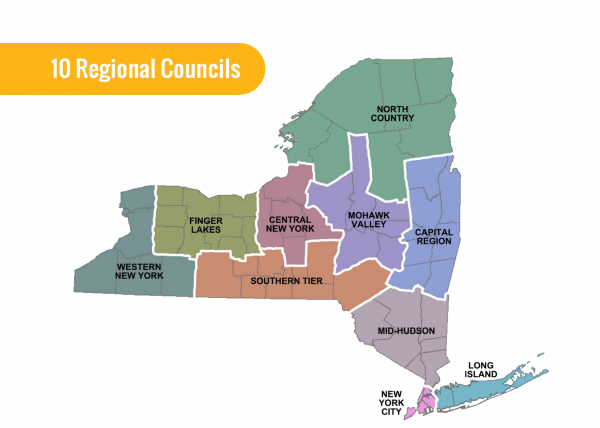

New York State is much more than just New York City, but the needs of the greater New York City area tend to dictate the policies enforced across the state. For purposes of this blog post, “Downstate” refers to the Long Island, New York City and Mid-Hudson regions shown in the above map. The remaining seven regions, Western New York, Finger Lakes, Central New York, Southern Tier, Mohawk Valley, North Country and the Capital Region, constitute “Upstate.” In reality, the boundaries between these two areas are more nuanced and controversial, but this generalized approach simplifies the point of this section: Upstate and Downstate New York differ significantly. The two population sizes and densities, economies, resources, and needs of Upstate are completely different than those of Downstate.

The five boroughs of New York City contain approximately 8.5 million people. The next populous city in New York is Buffalo, which has around 258,000 residents. https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/cities/new-york (last visited Nov. 2, 2020) (citing U.S. Census Annual Estimates at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-cities-and-towns.html). The wealth disparity is also dramatic. The counties in the Downstate area, with the exception of Bronx County, are much wealthier than the Upstate counties. See poverty rates by county at https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/united-states/quick-facts/new-york/percent-of-people-of-all-ages-in-poverty#map (last visited Nov. 2, 2020). Also see median household income by county at https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/united-states/quick-facts/new-york/median-household-income#map. It stands to reason that Downstate has a greater need for electricity generation than Upstate, and Upstate has more space to build solar and wind farms. It also stands to reason that the Upstate municipalities do not have the same financial resources as the Downstate municipalities and the over-arching State government. The economic disadvantages of Upstate has the potential to create a power differential between the two regions in their relation to the State government.

If the State government wants to move towards 70% renewable energy sourcing for all of New York by 2030, and New York does not want to depend entirely on other states for its energy, then a significant amount of renewable electric generation facilities must be constructed in the Upstate region in the coming years. The strategy of Upstate siting is very attractive, especially since the land is relatively inexpensive (in part because the sluggish economy of Upstate does not make it a desirable place to live). The State’s [renewable energy?] agenda will be implemented in Upstate, and under Public Service Law §168(3)(e), and, for better or for worse, there is very little Upstate communities and residents can do about it.

CURRENT LOCAL STATE OF AFFAIRS - NIMBY

I live in the Town of Rush, which is in the same county as the City of Rochester. My town is rural, but the county is largely urban and suburban. Currently, there is a strong disagreement about whether a large solar farm project should be sited in farm fields around the Town of Rush. One of the proposed sites abuts my neighborhood. My neighbors, some of whom live in homes built by a prominent local architect in the 1910’s, strongly oppose the solar project. Some Rush residents, including my neighbors, have formed a local interest group called “Residents United to Save our Hometown” (R.U.S.H. for short). https://rush-solar.com/ (last visited Nov. 2, 2020). This group advocates against the siting of a “Massive Solar Power Plant” in our town.

The neighboring towns have welcomed the solar projects with open arms. However, the solar company approached farmers in Rush about leasing their fields to expand the size of the project. The farmers are fully in support of the project, since the solar company would lease their fields for construction. I have not learned the exact leasing rate offers on the table, but I assume the revenue will be greater, or at least more consistent, than what is generated by the corn, hay and soy beans that are historically grown in these fields. Crop production is weather and climate dependent, relies heavily on government subsidies, and is labor intensive. Rental of land to a solar company would almost certainly be less work for the farmer and less economically volatile than agriculture.

On the other side, the R.U.S.H. group argues that the solar farm will disrupt local wildlife, especially since the project proposal includes 8-foot chain-link fences surrounding each solar field. It argues that solar panels are wasteful, since they need to be replaced every several years and proper disposal of the used panels is difficult. I have heard members claim that Upstate New York is an inappropriate location for industrial solar projects because it is very cloudy for most of the year. Most familiarly, R.U.S.H. also argues that the “massive solar plant” will “disrupt the rural character of our town.” This all boils down to a NIMBY problem – right now we have pleasant views of farm fields, and soon we may have views of a large solar farm with an 8-foot fence around it, and that is not acceptable to some residents.

Recently, members of the local Seneca Nation community have joined R.U.S.H. in its opposition. Steve Orr, Senecas join residents in opposing solar farm, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 23, 2020, at 4A. A town adjacent to Rush and within a mile of the proposed sites was the birthplace of a spiritual leader. Id. Furthermore, a bone was discovered at one of the proposed sites recently, though no experts have weighed in on whether the bone is human or non-human. Id. at 5A. This area was once populated by the Seneca Nation, but there does not seem to be much evidence that the proposed sites themselves were burial grounds, or otherwise sacred. Id.

While I appreciate the efforts of my neighbors, I, personally, am in support of the solar projects. The farms produce a lot of pollution that seeps off into the Genesee River, which runs by our properties on its way north to the City of Rochester. My neighbors’ and my vista of the farm is mostly obstructed by trees. Gaps could easily be filled with more trees so that we only see the farms when we drive in and out of our neighborhood. I also understand the concerns of the Seneca Nation advocates and am grateful they have spoken up. However, evidence is lacking that the sites themselves were sacred and/or significant to the Seneca. Furthermore, these sites are already industrially farmed. If they were important to the Seneca Nation, I do not understand why they would accept one use of the land and not another. Renewable energy is extremely important, and the cheap open land close to Rochester, New York is a great opportunity to at least move Upstate New York towards renewable energy sources. Even if New York City cannot convert to 70% renewables, I believe Upstate is well-positioned to meet that goal and even surpass it if the proper facilities are constructed.

ANALYSIS

New York State’s reenacted Article X eliminates NIMBY challenges to projects that are crucial to combatting climate change and reducing New York’s carbon emissions. Local laws that are altered to prevent siting can simply be ignored, and challenging the siting board’s decision to do so places the evidentiary burden on the local municipality. While it is helpful to avoid NIMBY challenges when an important shift in policy is the goal, the new Article X goes too far. It amplifies the power differential between rural municipalities and the State government and risks ignoring legitimate local challenges that may be more than just aesthetically-based.

Upstate New York NIMBY is not new. In fact, in Trude v. Town Board of the Town of Cohocton, a citizens group fought the siting of wind turbines in their town by arguing the importance of “maintaining the predominantly rural character of Cohocton…” among other reasons. Trude v. Town Bd. Of the Town of Cohocton, 17 Misc.3d 1104(A) (Sept. 24, 2007). The citizen’s group lost and the wind turbines were eventually built on the hills of Cohocton, which is 50 miles south of Rush. The failure of the citizens group in the Cohocton case is notable because that project went through the siting process between 2003 and 2011, which gave the local authorities more power in the decisions. Challenges to progressive energy solutions that are based clearly on preferential aesthetics are expensive, unproductive and, frankly, selfish. Slowing climate change and reducing pollution are absolutely worth the sacrifice of the view of a farm field outside my window. States have developed various siting processes to try to combat the NIMBY issue and other arbitrary road-blocks to increasing renewable electricity generation.

New York, however, has gone too far. The siting approval process under Article X guts any leverage the local municipalities and citizens thereof had in the past. The siting board still includes ad hoc local members, involves a public hearing and includes the intervenor fund. However, the local participation in the process is not meaningful in practical terms, largely because of the lack of resources of these rural counties in comparison to the State and utility company. The intervenor fund does not cover attorney fees, and it can only be spent to hire experts who will educate the local residents and municipality about the project. Therefore, the municipality or the interested local group must either pay out of pocket or apply for grants, assuming they can find a competent attorney to represent them.

There were problems with the process used between 2003 and 2011 as well. Local municipalities should not be the sole body, or even leading body, to determine the site of large electric generation projects. The local governments are made up of residents who likely do not have the expertise to a) follow the procedures laid out in state law, or b) understand the benefits, consequences and details involved with determining a proper site for a major electric generation facility. New York State has experts within the government and access to whatever advice it needs when it comes to the technical and legal aspects of facility siting. I do not argue that the previous regime should be reinstated, since the State has the resources and expertise (or access to expertise) to make the final decision regarding sites. That being said, local groups and municipalities should be included in a more meaningful way. Furthermore, residents with real estate near the facility sites should receive some benefit, whether in the form of mitigation or financial incentives.

Proposal #1 – Rebalance the Burden Scales

The burden of showing that a local law or regulation is not unreasonably burdensome should be changed. Perhaps the State Board should have to make a showing that project-inhibiting local rule is unreasonably burdensome, and then the burden could shift to the municipality to show that it is not. Minnesota’s siting laws require a “good cause” showing as to why the local law should be ignored. K.K. DuVivier & Thomas Witt, NIMBY to Nope-or Yesss?, 38 Cardozo L. Rev. 1453, 1488 (2017). While this does not solve the financial access to the courts issue in the rural New York counties, it does level the playing field a bit when a court case is initiated.

Proposal #2 – What’s in it for the Residents?

Gregory D. Eriksen emphasizes that NIMBY is a psychological response to a loss of control of one’s property, and giving locals more control or even a sense of control can reduce the frequency of these challenges. Gregory D. Eriksen, Breaking Wind, Fixing Wind: Facilitating Wind Energy Development in New York State, 60 Syr. L. Rev. 189, 196 (2009). To add insult imbalance of power injury, residents living near the facility sites seem to be the only party not benefiting financially from the project. The solar companies earn profits from the electricity generated and sold, and they receive tax incentives from New York State. The farmers receive good, steady income from the solar companies. The municipalities receive tax revenue from the solar companies. The State receives tax revenue from the solar companies, gains political capital for converting to “renewables,” and, ideally, helps reduce global emissions and, therefore, reduce the costs of climate change adaptation measures. Residents receive the same benefit as the global community – reduction in emissions, which hopefully compounds to slow climate change. Residents who live closest to the sites receive the same benefits as those who live across town with relation to the increased municipality revenue. Schools may have more money, roads may be in better shape, but the residents bearing the brunt of the project are not acknowledged independently. Some mitigation or benefit provision to these residents may reduce the number of NIMBY challenges.

A mitigation to the NIMBY challenge to solar fields in particular could be to require the solar companies to plant trees around the fields, instead of or in addition to the fencing. This strategy may quell residents who are concerned about the view from their windows – trees are preferable to chain-link fences and solar panels, if they can be planted in a way that does not obstruct the sunlight from reaching the panels.

The State could offer residents a tax break for properties within a certain distance from the project. Residents are often concerned about the value of their real estate plummeting because of a large solar project. Property taxes in New York State are very high, so any additional tax relief would be welcomed by landowners and may reduce the number of disgruntled NIMBY proponents.

The solar company could provide incentives related to the electrical services to nearby landowners. Electricity in rural areas can be expensive. Perhaps a reduction in electricity costs would satisfy some residents. Even a promise to convert all nearby residents to renewably-sourced electricity (a privilege for which we must pay extra currently) may change minds.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the current system under Article X is too heavily weighted towards the State and utility companies. While NIMBY challenges to renewable energy projects are frustrating and inefficient, the State has gutted locals of all power to challenge these projects just to avoid the aggravation of NIMBY. The State should remain largely in control of siting decisions, because the local municipalities do not always have access to the same resources and experts when compared to the State. However, the scales on the burden of establishing whether a local law is “unreasonably burdensome” should lie with the State. Local municipalities should not have the burden to prove their laws are not unreasonably burdensome.

Furthermore, I theorize that many NIMBY challenges are more about control and “what’s in it for me?” responses to change. Providing a benefit to local residents, or mitigating the aesthetic impact of a project could reduce the number of NIMBY challenges. Some individuals will always combat change in their communities, but if residents generally feel less ignored or excluded from the positive aspects of the project, I believe many will shift from opposition to support of large renewable electric facilities in their backyard.

Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law is located in Wood Hall on the Law Campus.

MSC: 51

email elaw@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-6649

Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC 51

Portland OR 97219